Building resilient applications with Polly

This is a cross-post from stackify.com.

Handling errors properly have always been an important and delicate task when it comes to making our applications more reliable. It is true that we can’t know when an exception will happen, but it is true that we can control how our applications should behave under an undesirable state, such as a handled or unhandled exception scenario. When I say that we can control the behavior when the application fails, I’m not only referring to logging the error; I mean, that’s important, but it’s not enough!

Nowadays with the power of cloud computing and all of its advantages, we can build robust, high availability and scalable solutions, but cloud infrastructure brings with its own challenges as well, such as transient errors. It is true that transient faults can occur in any environment, any platform or operating system, but transient faults are more likely in the cloud due to its nature, for instance:

- Many resources in a cloud environment are shared, so in order to protect those resources, access to them is subject to throttling, which means they are regulated by a rate, like a a maximum throughput or a specific load level; that’s why some services could refuse connections at a given point of time.

- Since cloud environments dynamically distribute the load across the hardware and infrastructure components, and also recycle or replace them, services could face transient faults and temporary connection failures occasionally.

- And the most obvious reason is the network condition, especially when communication crosses the Internet. So, very heavy traffic loads may slow communication, introduce additional connection latency, and cause intermittent connection failures.

Challenges

In order to achieve resilience, your application must able to respond to the following challenges:

- Determine when a fault is likely to be transient or a terminal one.

- Retry the operation if it determines that the fault is likely to be transient, and keep track of the number of times the operation was retried.

- Use an appropriate strategy for the retries, which specifies the number of times it should retry and the delay between each attempt.

- Take needed actions after a failed attempt or even in a terminal failure.

- Be able to fail faster or don’t retry forever when the application determines the transient fault is still happening or it turns out the fault isn’t transient. In a cloud infrastructure, resources and time are valuable and have a cost, so you might not want to waste time and resources trying to access a resource that definitively isn’t available.

At the end of the day, if we are guaranteeing resiliency, implicitly we are guaranteeing reliability and availability. Availability, when if it comes to a transient error, it means the resource is still available, so, we shouldn’t merely respond with an exception. So that’s why it is so important to have in mind these challenges and handle them properly in order to build a better software. This is where Polly comes into play!

What is Polly?

Polly is a .NET resilience and transient-fault-handling library that allows developers to express policies such as retry, circuit breaker, timeout, bulkhead isolation, and fallback in a fluent and thread-safe manner.

Getting started

I won’t explain the basic concepts/usage of every feature because the Polly project already has great documentation and examples. My intention is to show you how to build consistent and powerful resilient strategies based on real scenarios and also share with you, my experience with Polly (which have been great so far).

So, we’re going to build a resilient strategy for SQL executions, more specifically, for Azure SQL databases. However at the end of this post, you will see that you could build your own strategies for whatever resource or process you need to consume following the pattern which I’m going to explain, for instance, you could have a resilient strategy for Azure Service Bus, Redis, Elasticsearch executions, etc. The idea is to build specialized strategies since all of them have different transient errors and different ways to handle them. Let’s get started!

Choosing the transient errors

The first thing we need to care about is to be aware of what are the transient errors for the API/Resource we’re going to consume, in order to choose which ones we’re going to handle. Generally, we can find them in the official documentation of the API. In our case, we’re going to pick up some transient errors based on the official documentation of Azure SQL databases.

- 40613: Database is not currently available.

- 40197: Error processing the request; you receive this error when the service is down due to software or hardware upgrades, hardware failures, or any other failover problems.

- 40501: The service is currently busy.

- 49918: Not enough resources to process the request.

- 40549: Session is terminated because you have a long-running transaction.

- 40550: The session has been terminated because it has acquired too many locks.

So, in our example, we’re going to handle the above SQL exceptions, but of course, you can handle the exceptions as you need.

The power of PolicyWrap

As I said earlier, I won’t explain the basics of Polly, but I would say that the building block of Polly is the policy. So, what’s a policy? Well, I would say a policy is the minimum unit of resilience. Having said that, Polly offers multiple resilience policies, such as Retry, Circuit-breaker, Timeout, Bulkhead Isolation, Cache and Fallback, These can be used individually to handle specific scenarios, but when you put them together, you can achieve a powerful resilient strategy, and this is where PolicyWrap comes into play.

PolicyWrap enables you to wrap and combine single policies in a nested fashion in order to build a powerful and consistent resilient strategy. So, think about this scenario:

When a SQL transient error happens, you need to retry for maximum 5 times but, for every attempt, you need to wait exponentially; for example, the first attempt will wait for 2 seconds, the second attempt will wait for 4 seconds, etc. before trying it again. But you don’t want to waste resources for new incoming requests, waiting and retrying when you already have retried 3 times and you know the error persists; instead, you want to fail faster and say to the new requests: “Stop doing it, it hurts, I need a break for 30 seconds”. It means, after the third attempt, for the next 30 seconds, every request to that resource will fail fast instead of trying to perform the action.

Also, given that we’re waiting for an exponential period of time in every attempt, in the worst case, which is the fifth attempt, we will have waited more than 60 seconds + the time it takes the action itself, so, we don’t want to wait “forever”, instead, let’s say, we’re willing to wait up to 2 minutes trying to execute an action, thus, we need an overal timeout for 2 minutes. Finally, if the action failed either because it exceeded the maximum retries or it turned out the error wasn’t transient or it took more than 2 minutes, we need a way to degrade gracefully, it means, a last alternative when everything goes wrong.

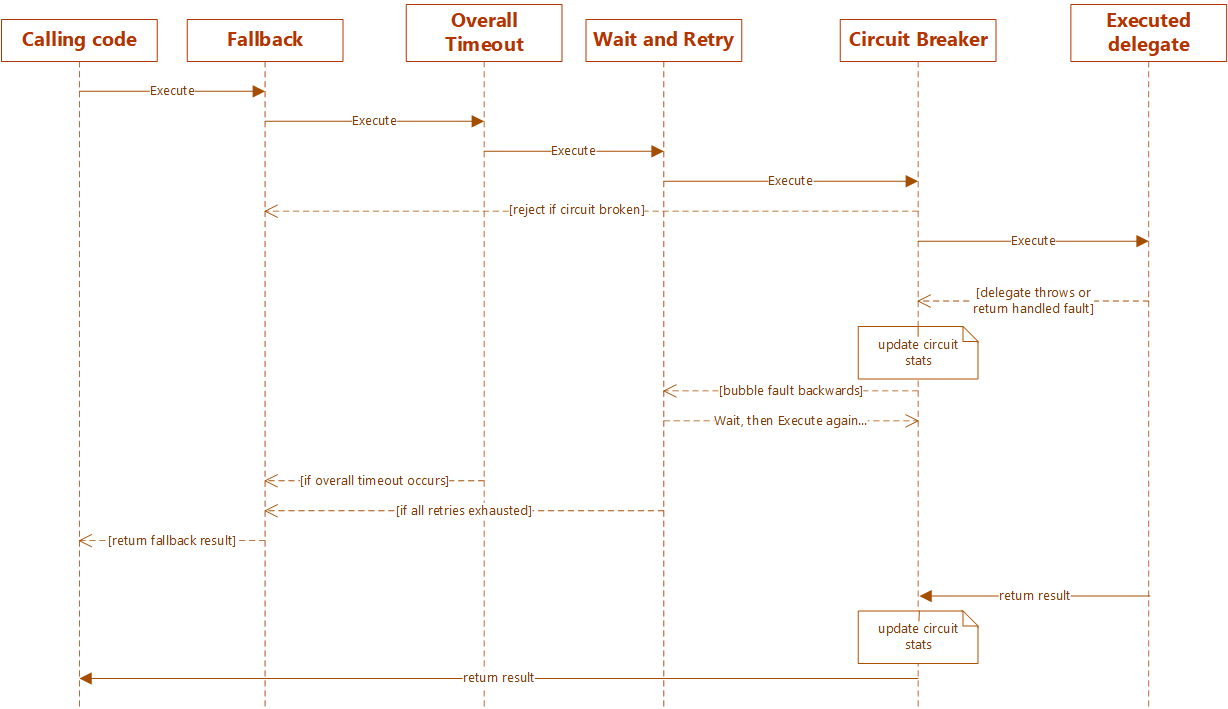

So if you noticed, to achieve a consistent resilient strategy to handle that scenario, we will need at least 4 policies, such as Retry, Circuit-breaker, Timeout and, Fallback but, working as one single policy instead of each individually. Let’s see how the flow of our policy would look to understand better how it will works:

Sync vs Async Policies

Before we start defining the policies, we need to understand when and why to use sync/async policies and the importance of not mixing sync and async executions. Polly splits policies into Sync and Async ones, not only for the obvious reason that separating synchronous and asynchronous executions in order to avoid the pitfalls of async-over-sync and sync-over-async approaches, but for design matters because of policy hooks, it means, policies such as Retry, Circuit Breaker, Fallback, etc. expose policy hooks where users can attach delegates to be invoked on specific policy events: onRetry, onBreak, onFallback, etc. But those delegates depend on the kind of execution, so, synchronous executions expect synchronous policy hooks, and asynchronous executions expect asynchronous policy hooks. This is an issue on Polly’s repo where you can find a great explanation about what happens when you execute an async delegate through a sync policy.

Defining the Policies

Having said that, we’re going to define our policies for both scenarios, synchronous and asynchronous.Also we’re going to use PolicyWrap, which needs two or more policies to wrap and process them as a single one. So, let’s take a look at every single policy.

I’ll only show you the async ones in order to simplify, but you can see the whole implementation for both, sync and async ones; the differences are, that the sync ones, executes the policy sync overload and the async ones, executes the policy async overload. Also, for the policy hooks with fallback policies, the sync fallback expect synchronous delegate while the async fallback expects a task.

Wait and Retry

We need a policy that waits and retries for transient exceptions that we already chose to handle earlier. So, we’re telling Polly to handle SqlExceptions but, only for very specific exception numbers. Also we’re telling how many times it should wait for and the delay between each attempt through an exponential back-off based on the current attempt.

public static IAsyncPolicy GetCommonTransientErrorsPolicies(int retryCount) =>

Policy

.Handle<SqlException>(ex => SqlTransientErrors.Contains(ex.Number))

.WaitAndRetryAsync(

// number of retries

retryCount,

// exponential back-off

retryAttempt => TimeSpan.FromSeconds(Math.Pow(2, retryAttempt)),

// on retry

(exception, timeSpan, retries, context) =>

{

if (retryCount != retries)

return;

// only log if the final retry fails

var msg = $"#Polly #WaitAndRetryAsync Retry {retries}" +

$"of {context.PolicyKey} " +

$"due to: {exception}.";

Log.Error(msg, exception);

})

.WithPolicyKey(PolicyKeys.SqlCommonTransientErrorsAsyncPolicy);

Circuit Breaker

With this policy, we’re telling Polly that after a determined number of exceptions in a row, it should fail fast and should keep the circuit open for 30 seconds. As you can see, there’s a difference in the way that we handle the exceptions; in this case, we have one single circuit breaker for each exception, due to circuit breaker policy counts all faults they handle as an aggregate, not separately. So we only want to break the circuit after N consecutive actions executed through the policy have thrown a handled exception, let’s say DatabaseNotCurrentlyAvailable exception, and not for any of the exceptions handled by the policy. You can check this out on Polly’s repo.

public static IAsyncPolicy[] GetCircuitBreakerPolicies(int exceptionsAllowedBeforeBreaking)

=> new IAsyncPolicy[]

{

Policy

.Handle<SqlException>(ex => ex.Number == (int)SqlHandledExceptions.DatabaseNotCurrentlyAvailable)

.CircuitBreakerAsync(

// number of exceptions before breaking circuit

exceptionsAllowedBeforeBreaking,

// time circuit opened before retry

TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30),

OnBreak,

OnReset,

OnHalfOpen)

.WithPolicyKey($"F1.{PolicyKeys.SqlCircuitBreakerAsyncPolicy}"),

Policy

.Handle<SqlException>(ex => ex.Number == (int)SqlHandledExceptions.ErrorProcessingRequest)

.CircuitBreakerAsync(

// number of exceptions before breaking circuit

exceptionsAllowedBeforeBreaking,

// time circuit opened before retry

TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30),

OnBreak,

OnReset,

OnHalfOpen)

.WithPolicyKey($"F2.{PolicyKeys.SqlCircuitBreakerAsyncPolicy}"),

.

.

.

};

Timeout

We’re using a pessimistic strategy for our timeout policy, which means it will cancel delegates that have no builtin timeout and do not honor cancellation. So this strategy enforces a timeout, guaranteeing to still returning to the caller on timeout.

public static IAsyncPolicy GetTimeOutPolicy(TimeSpan timeout, string policyName) =>

Policy

.TimeoutAsync(

timeout,

TimeoutStrategy.Pessimistic)

.WithPolicyKey(policyName);

Fallback

As defined earlier, we need a last chance when everything goes wrong; that’s why we’re handling not only the SqlException, but TimeoutRejectedException and BrokenCircuitException. That means if our execution fails either because the circuit is broken, it exceeded the timeout, or it throws a Sql transient error, we will be able to perform a last action to handle the imminent error.

public static IAsyncPolicy GetFallbackPolicy<T>(Func<Task<T>> action) =>

Policy

.Handle<SqlException>(ex => SqlTransientErrors.Contains(ex.Number))

.Or<TimeoutRejectedException>()

.Or<BrokenCircuitException>()

.FallbackAsync(cancellationToken => action(),

ex =>

{

var msg = $"#Polly #FallbackAsync Fallback method used due to: {ex}";

Log.Error(msg, ex);

return Task.CompletedTask;

})

.WithPolicyKey(PolicyKeys.SqlFallbackAsyncPolicy);

Putting all together with Builder pattern

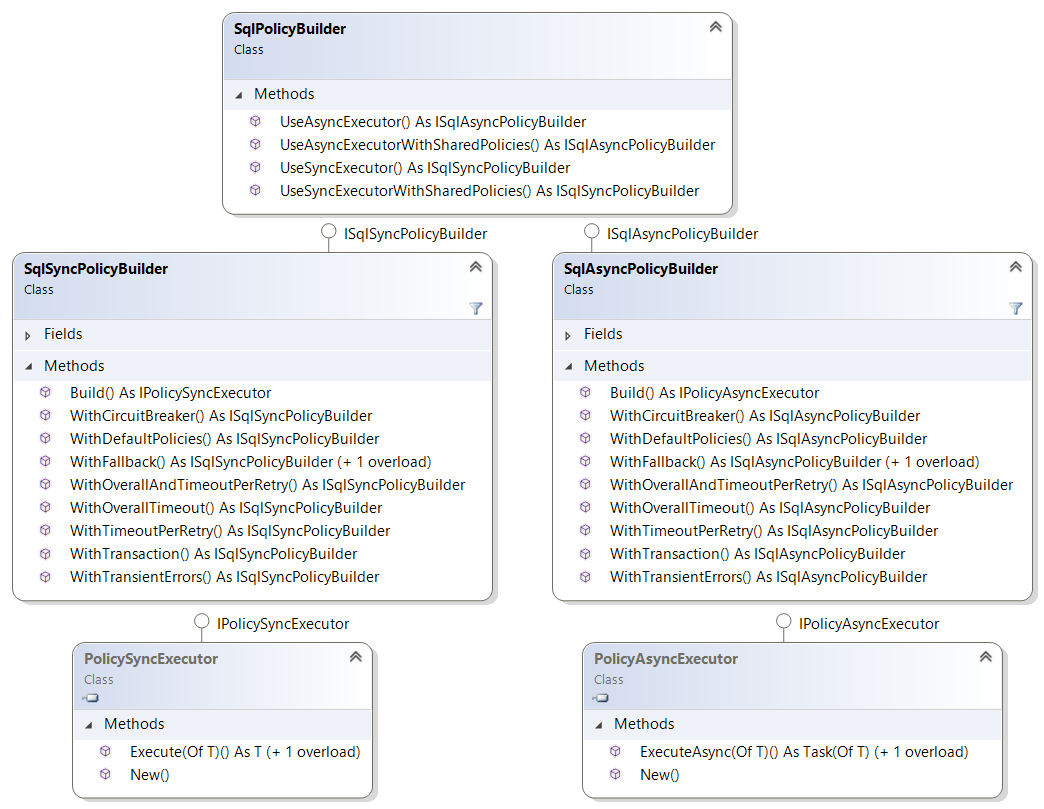

Now that we already have defined our policies, we need a flexible and simple way to use them, that’s why we’re going to create a builder in order to make our resilient strategies easier to consume. So the idea to make a builder is we can use either sync or async policies transparently and without caring too much about implementations, and also in order to be able to build our resilient strategies at convenience, mixing the policies as we need them. So, let’s take a look at the builder model; it’s pretty simple but pretty useful as well.

Basically, we have two policy builder implementations, one for sync and another for async ones, but the nice point is we don’t have to care which implementation we need to reference or instantiate in order to consume it. We have a common SqlPolicyBuilder that gives us the desired builder through its UseAsyncExecutor or UseSyncExecutor methods.

So every builder (SqlAsyncPolicyBuilder and SqlSyncPolicyBuilder) exposes methods that allow us to build a resilient strategy in a flexible way. For instance, we can build the strategy to handle the scenario defined earlier, like this:

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithFallback(async () => result = await DoFallbackAsync())

.WithOverallTimeout(TimeSpan.FromMinutes(2))

.WithTransientErrors(retryCount: 5)

.WithCircuitBreaker(exceptionsAllowedBeforeBreaking: 3)

.Build();

result = await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

return await DoSomethingAsync();

});

In the previous example, we built a strategy that exactly fits the requirements of our scenario, and it was pretty simple, right? So we’re getting an instance of ISqlAsyncPolicyBuilder through the UseAsyncExecutor method. Then we’re just playing with the policies that we already defined earlier, and finally, we’re getting an instance of IPolicyAsyncExecutor that takes care of to the execution itself; it receives the policies to be wrapped and executes the delegate using the given policies.

Policy order matters

In order to build a consistent strategy, we need to pay attention to the order that we wrap the policies. As you noticed in our resilience strategy flow, the fallback policy is the outermost and the circuit breaker is the innermost since we need the first link in the chain to keep trying or fail fast, and the last link in the chain will degrade gracefully. Obviously, it depends on your needs, but for our case, it would make sense to wrapp the circuit breaker with a timeout? That’s what I mean when I say policy order matters and why I named the the policies alphabetically using the WithPolicyKey method; inside the Build method I sort the policies in order to guarantee a consistent strategy. Take a look at these usage recommendations when it comes to wrapping policies.

Sharing policies across requests

We might want to share the policy instance across requests in order to share its current state. For instance, it would be very helpful when the circuit is open, in order for the incoming requests fail fast instead of wasting resources trying to execute a delegate against to a resource that currently isn’t available. Actually, that’s one of the requirements of our scenario. So our SqlPolicyBuilder has the UseAsyncExecutorWithSharedPolicies and UseSyncExecutorWithSharedPolicies methods, which allow us to reuse policy instances that are already in use instead of creating them again. This happens inside the Build method and the policies are stored/retrieved into/from a PolicyRegistry. Take a look at this discussion and the official documentation to see what policies share the state across requests.

Other usage examples of strategies with our Builder

You can find several integration tests here, where you can take a look at the behavior of resilient strategies given a specific scenario, but let’s going to see a few common strategies here as well.

WithDefaultPolicies

There’s a method called WithDefaultPolicies that makes it easier building the policies; it creates an overall timeout, wait and retry for SQL transient errors, and the circuit breakers policies for those exceptions; that way, you can consume your most common strategy easily.

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithDefaultPolicies()

.Build();

result = await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

return await DoSomethingAsync();

});

// the analog strategy will be:

resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithOverallTimeout(TimeSpan.FromMinutes(2))

.WithTransientErrors(retryCount: 5)

.WithCircuitBreaker(exceptionsAllowedBeforeBreaking: 3)

.Build();

WithTimeoutPerRetry

This allows us to introduce a timeout per retry, in order to handle not only an overall timeout but the timeout of each attempt. So in the next example, it will throws a TimeoutRejectedException if the attempt takes more than 300 ms.

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithDefaultPolicies()

.WithTimeoutPerRetry(TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(300))

.Build();

result = await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

return await DoSomethingAsync();

});

WithTransaction

This allows us to handle SQL transient errors related to transactions when the delegate is executed under a transaction.

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithDefaultPolicies()

.WithTransaction()

.Build();

result = await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

return await DoSomethingAsync();

});

To have in mind

Avoid wrapping multiple operations or logic inside executors, especially when they aren’t idempotent, or it could be a mess. Think about this scenario:

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithDefaultPolicies()

.Build();

await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

await CreateSomethingAsync();

await UpdateSomethingAsync();

await DeleteSomethingAsync();

});

In the previous scenario if something went wrong, let’s say into the UpdateSomethingAsync or DeleteSomethingAsync operations, the next retry will try to execute CreateSomethingAsync or UpdateSomethingAsync methods again, which could be a mess; so for cases like that, we have to make sure that every operation wrapped into the executor will be idempotent, or we have to make sure to wrap only one operation at a time. Also, you could handle that scenario like this:

var builder = new SqlPolicyBuilder();

var resilientAsyncStrategy = builder

.UseAsyncExecutor()

.WithDefaultPolicies()

.Build();

await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

await CreateSomethingAsync();

});

await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

await UpdateSomethingAsync();

});

await resilientAsyncStrategy.ExecuteAsync(async () =>

{

await DeleteSomethingAsync();

});

Wrapping up

As you can see, it is pretty easy and useful from the consumer point of view to use the policies through a builder because it allows us to create diverse strategies, mixing policies as we need in a fluent manner. So I encourage you to make your own builders in order to specialize your policies; as we said earlier, you can follow these patterns/suggestions to make your builders, let’s say, for Redis, Azure Service Bus, Elasticsearch, HTTP, etc. The key point is to be aware that if we want to build resilient applications, we can’t treat every error just as an Exception; every resource in every scenario has its own exceptions and a proper way to handle them.

Take a look at the whole implementation on my GitHub repo: https://github.com/vany0114/resilience-strategy-with-polly